Many of us will remember the New Atheism that was greatly prevalent in the media twenty years ago, largely promoted by the group known as the ‘Four Horsemen’ being Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris and Daniel Dennett who sought to promote a strongly secular, scientifically rational worldview which was quite independent of religious faith. Ironically, their strident tone often had qualities of ‘religious zeal’ about it which was off-putting to some and conveniently overlooked the fact that many exemplary scientists were Christians who saw absolutely no conflict between their religious faith and the science they pursued. However, in recent times, it’s become quite clear that life requires more than just science to guide it – as so eloquently and poignantly expressed by the American environmental lawyer, James Gustave Speth who said:

“I used to think the top global environmental problems were biodiversity loss, ecosystem collapse and climate change. I thought that with 30 years of good science we could address these problems. But I was wrong. The top environmental problems are selfishness, greed and apathy, and to deal with these we need a spiritual and cultural transformation, and we scientists don’t know how to do that.”

— James Gustave Speth, Shared Planet: Religion and Nature, BBC Radio 4 (1 October 2013)

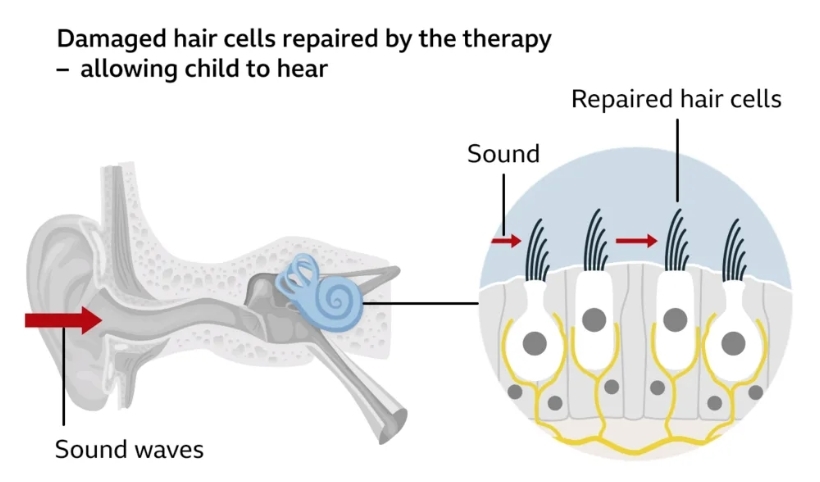

Indeed, just recently our own Bishop of Norwich, The Rt Revd Graham Usher, who is the Archbishop of Canterbury’s lead ‘Bishop for the Environment’, reminded clergy that “science and theology nurture one another- they should not be seen as combatants!” – Norwich Cathedral (8th July 2025). John Polkinghorne, the former Physicist turned Anglican Priest also said that “Science tells us how things work; theology tells us why things matter” – and in a deeply uncertain world we need both; science seeking understanding – while faith offers meaning.

So why do so many of us still struggle to hold these two things together? Is it because past historical moments, such as the New Atheism period, have left us feeling that we can’t express our Christian faith without people doubting our intelligence? Fortunately, the tide is turning, and people are appreciating that many Christians, including scientists, are thoughtful rational people whose faith is deeply enhanced by their logical approach to life. Indeed, one such person is Prof. YoungHoon Kim from South Korea who with a staggeringly high score of 276 is recognised as having the highest recorded IQ in the world, which is higher than other notable minds such as Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking. Prof. Kim, who studies Quantum Physics, is also a devout Christian and sees theology not as blind faith but as a rigorous discipline and the ‘ultimate field of study’.

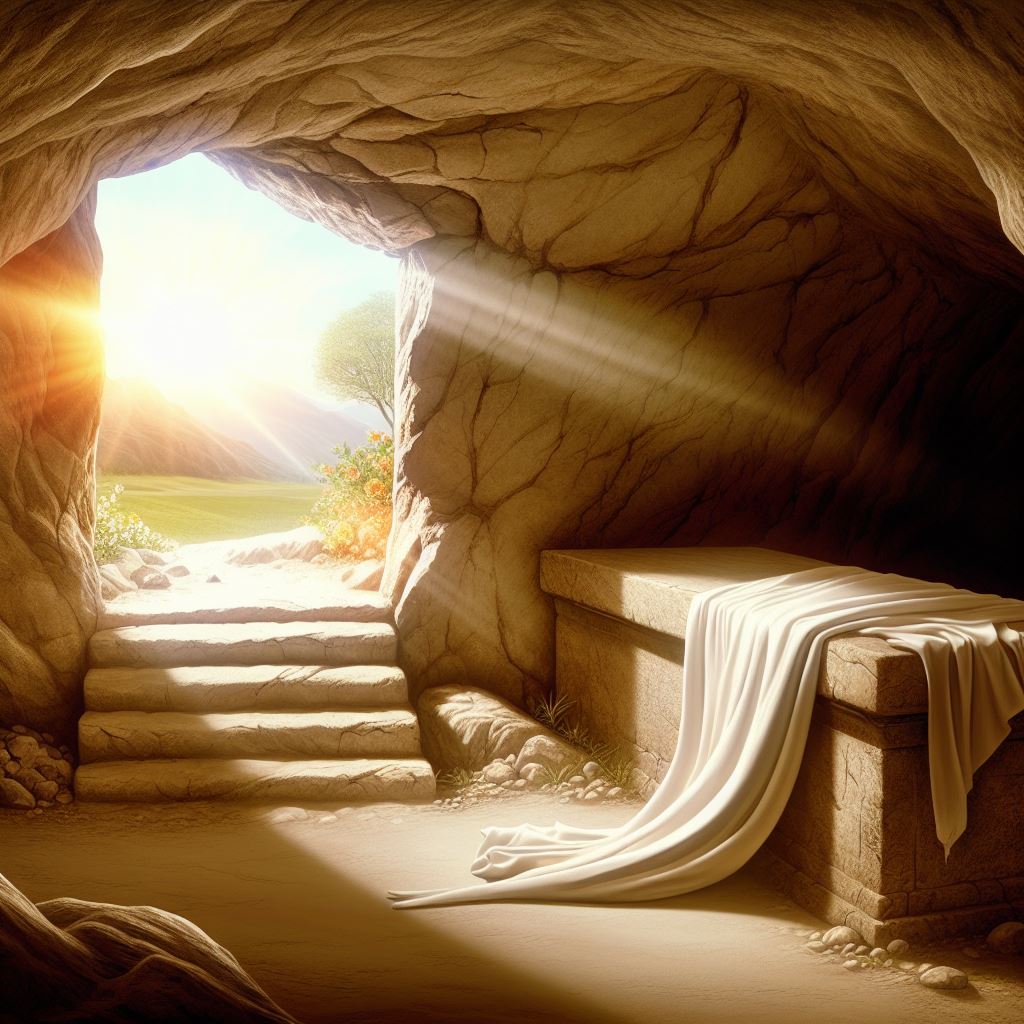

But of course, the beautiful thing about the Bible and the Gospel story of Jesus Christ is that on one level it can be explained so simply that even a little child can understand it, but on another level, it can also be so profound that it satisfies the deepest of intellectual minds. Perhaps the problem with the New Atheists was not that they weren’t brilliant men – but that they underestimated the intelligence and vision of faithful believers.

With best wishes. Stephen Thorp

The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom; all who follow his precepts have good understanding.

Psalm 111.10

This article first appeared in the August edition of Parish Magazines associated with the Necton Benefice – Parish Link; Moonraker; The Pickenhams’

If you would like to support the ministry of the Necton Benefice or make a one-off donation this QR code will take you to the appropriate website – Thank you and God bless